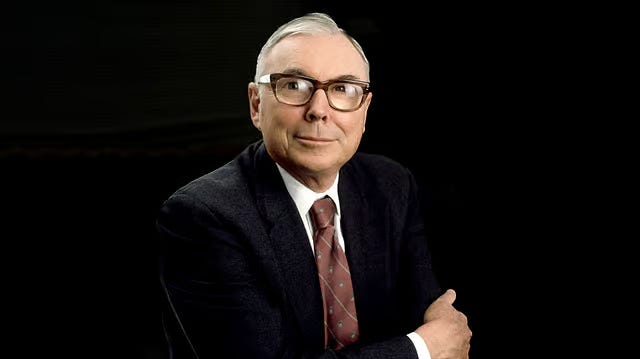

Charlie Munger

Ben and David sit down with the legendary Charlie Munger months before his death in the only dedicated longform podcast interview that he has done in his 99 years on Earth.

Kyle’s Rating: 7/10

This interview’s intimate atmosphere—like sharing a seat at Charlie Munger’s dinner table—creates a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for Ben and David to absorb his razor-sharp wisdom firsthand. Yet Munger’s sometimes terse and mechanical responses create an uneven rhythm, forcing the hosts to work harder to unlock his deeper insights. As an admirer of Poor Charlie’s Almanack, I treasure any glimpse into Munger’s profound thinking, even when the format doesn’t fully showcase his intellectual depth.

Charlie Munger

Charlie Munger, the legendary investor and vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, is a titan of value investing and multidisciplinary thinking, profoundly influencing business philosophy through his nearly 50-year partnership with Warren Buffett. This interview was conducted a few months before his death. At 99 during this interview, Munger has incisive observations on markets, human behavior, and societal evolution, delivered with wit and unflinching realism that distill a century of experience into timeless lessons.

Ben and David (with contributions from Andrew Marks) this interview—likely Munger’s only longform podcast—explores his career, from early investment triumphs to critiques of modern markets. It delves into his advocacy for Costco, insights on partnerships, life advice at nearly 100, and candid quotes reflecting his contrarian ethos. Ben and David engage Munger with reverence and curiosity, coaxing his famed “speech on the virtues of Costco” while extracting universal wisdom, creating a narrative that’s both intimate and profound, akin to a masterclass over dinner.

Key Topics

Gambling vs. True Investing

Context: Ben sparks the discussion with concerns about sports betting ads during NFL games, prompting Munger to critique gambling industries and retail stock trading.

Analysis: Munger equates casinos and racetracks to societal detriments, contrasting them with disciplined investing where odds favor the “house,” as Buffett practiced. He lambasts retail trading as uninformed price speculation, akin to gambling, and proposes taxing short-term gains without loss offsets to deter speculators. This reflects his value investing ethos, emphasizing knowledge and patience over quick wins, shaped by decades of navigating markets with Buffett. His influence lies in warning against market frenzy, protecting long-term wealth in a world of fading opportunities.

Algorithmic Trading and Leverage Risks

Context: Andrew asks about algorithms like Renaissance Technologies, leading Munger to dissect their mechanics and risks.

Analysis: Munger explains Renaissance’s early success exploiting market patterns (e.g., trend-following) but criticizes modern reliance on extreme leverage for shrinking returns, a risk he’d avoid as “crazy” for the wealthy. This ties to his conservative temperament, shaped by Berkshire’s low-leverage strategy and close calls like Salomon Brothers, prioritizing safety over aggressive plays. His disdain for over-optimization influences ethical finance, highlighting misaligned incentives in high-leverage models. “They’re making smaller and smaller profits off more and more volume, which gives them this big peak leverage risk, which I would not run myself.”

Virtues of Costco and Retail Models

Context: Ben’s conversation with Costco’s Richard Galanti leads Munger to recount meeting Sol Price and deliver his “speech on the virtues of Costco.”

Analysis: Munger praises Costco’s low-SKU, high-turnover, capital-light model—no inventory on books, wide parking, supplier financing—as a rare edge executed with “fanaticism” over decades. He highlights its success (e.g., targeting wealthy customers) and imitators like Home Depot, while noting Walmart’s failure due to entrenched habits. His board tenure and push for China expansion reflect conviction in rare opportunities, urging heavy bets when certain. This epitomizes his philosophy of seizing obvious edges, a cornerstone of his retail investment legacy. “There aren’t many times in a lifetime when you know you’re right and you know you have one that’s really going to work wonderfully. Maybe five or six times in a lifetime you get a chance to do it.”

Early Retail Investments and Lessons

Context: Discussions on Costco lead to Munger’s history with Diversified Retail and Blue Chip Stamps.

Analysis: Munger recounts reversing a poor department store buy to repurchase stocks during recessions, tripling value, and flipping a $20M savings and loan into $2B for Berkshire’s insurance capital. Buffett’s retail aversion, rooted in its competitiveness (e.g., Sears’ fall), contrasts with Munger’s Costco advocacy. These “wonderful early years” highlight adaptability—turning mistakes into gains—and the scarcity of such low-hanging fruit today, shaping his pragmatic approach to capital allocation. “We just, in the middle of one of those recessions, we just bought, bought, bought, and bought. All that money went right into those stocks. Of course, we tripled it just sitting on our ass.”

Partnership with Warren Buffett

Context: Ben and David seek advice on their 10-year partnership, contrasting with Munger’s 50-year bond with Buffett.

Analysis: Munger credits early low-hanging fruit and shared values—prioritizing shareholder safety—for Berkshire’s scale, noting more leverage could have tripled wealth but risked the franchise. Mutual liking, complementary skills, and trust sustained their bond, with distance aiding longevity but early time together building rapport. He advises enjoying work and dividing labor naturally, reflecting a temperament-driven approach that values independence and trust over formulas. “Warren still cares more about the safety of his Berkshire shareholders than he cares about anything else. If we used a little bit more leverage throughout, we’d have three times as much now, and it wouldn’t have been that much more risk either.”

Critiques of Venture Capital

Context: David probes Munger’s views on venture capital’s societal role.

Analysis: Munger calls consistent VC wins “all but impossible” due to hot deals and gambling-like decisions, slamming 2-and-20 fees for enriching managers while harming investors. Contrasting Berkshire’s no-sell ethos, he notes endowments’ pushback (e.g., pari passu terms halving fees) reflects distrust. He sees legitimate VCs as rare nurturers, not manipulators, aligning with his preference for self-funded independence post-wealth. “You don’t want to make money by screwing your investors and that’s what a lot of venture capitals do.”

Bitcoin and Global Currencies

Context: Ben raises Bitcoin’s role in cross-border transfers and unstable economies.

Analysis: Munger dismisses Bitcoin as redundant, favoring the dollar’s fungibility and global reserve status (e.g., China’s dollar holdings). His trust in established systems over novelties reflects a conservative temperament honed by historical currency shifts (e.g., pound to dollar). This pragmatic stance prioritizes stability, dismissing crypto’s hype while acknowledging the dollar’s accessibility even in less fortunate nations. “The dollar is very fungible, you can always buy one anywhere.”

Japanese Trading Houses Investment

Context: Andrew asks about Berkshire’s stakes in Japanese trading houses.

Analysis: Munger calls it a “no-brainer” due to low rates (0.5% for 10 years), entrenched assets, and 5% dividends, enabled by Berkshire’s credit and patient $10B accumulation. Such rarities (2-3 per century) reward intelligence, effort, and luck, reflecting his opportunistic style. He stresses the difficulty of scaling such bets, even for Berkshire, underscoring the scarcity of easy wins today. “It was like God just opening a chest and just pouring money. It’s awfully easy money.”

Brands and Pricing Power

Context: Costco’s Kirkland leads to discussions on See’s Candy, Hermes, and Heinz ketchup.

Analysis: Munger lauds brands enabling 10% annual price hikes (See’s: $4M pretax to billions) due to loyalty, like Heinz’s ketchup flavor versus Kraft’s cheese. He avoids “style” companies (e.g., Nike) unless cheap, preferring timeless edges like Hermes’ century-built trust. This distills his value creation insight—buy rare brands at low prices—shaped by retail failures like Sears. Referring to See’s Candies, he says: “We’ve been raising the price by 10% a year for all these 40 years or so. It’s been a very satisfactory company.”

Investments in China and BYD

Context: Questions on China risks and BYD’s rise.

Analysis: Munger sees China’s economy and firms as superior and cheaper, justifying 18% portfolio exposure. BYD’s $270M to $8B reflects its electric vehicle dominance, driven by a “genius” founder closer to execution than Elon Musk, though aggressive growth unnerves him. “The guy was a genius... He is a natural engineer and a get-it-done type production executive.”

Key Quotes

Quote: “The beauty of it is: you only have to get rich once. You don’t have to climb this mountain four times. You just have to do it once.” (Munger)

Context: Responding to Andrew on scarce opportunities.

Explanation: Munger emphasizes patience and conviction, urging focus on rare wins in a harder world, reflecting his life-long strategy.

Quote: “Three things: They’re very intelligent, they worked very hard, and they were very lucky. It takes all three to get them on this list of the super successful.” (Munger)

Context: On super-success factors, applied to himself and Buffett.

Explanation: Munger demystifies achievement as intelligence, effort, and luck, advocating humility over hubris.

Quote: “It’s not so damn easy just to go out... if you go to the ordinary person trying to promote himself as an investment advisor... We don’t feel that way.” (Munger)

Context: Wrapping up with life reflections.

Explanation: Contrasts genuine expertise with pretenders, urging realism in a noisy world.

Quote: “A young man knows the rules, and an old man knows the exceptions.” (Munger, via Peter Kaufman)

Context: Ben asks about life’s exceptions.

Explanation: Highlights wisdom from experience, like Costco’s hotdog pricing anomaly, reflecting flexible principles.

Quote: “The best way to have a great spouse is to deserve one.” (Munger, via David)

Context: Family-building advice for Ben and David.

Explanation: Stresses mutual trust and effort, extending to education and challenges.

Related Episode

Berkshire Hathaway Part II (Season 8, Episode 6)

Costco (Season 13, Episode 2)

Walmart (Season 11, Episode 1)