Rolex

Their products are comparable to a Hermès Birkin bag in price, luxury status and waitlist times… yet they produce over 1m units / year (roughly 10x annual Birkin production).

Rolex is a series of paradoxes. They sell obsolete and objectively inferior mechanical devices for 10-1000x the price of their superior digital successors… and demand is stronger than ever in history! Their products are comparable to a Hermès Birkin bag in price, luxury status and waitlist times… yet they produce over 1m units / year (roughly 10x annual Birkin production). They make the most universally recognized and desired Swiss watches… yet their founder wasn’t Swiss and didn’t start the company in Switzerland! If Rolex were publicly traded, they’d almost certainly be among the top 50 market cap companies in the world… yet they’re 100% owned by a charitable foundation in Geneva that (among other things) literally just gives away money to local people in the city.

This is one of the most fascinating and admirable companies Ben and David have ever covered on Acquired.

Kyle’s Rating: 10/10

This episode clearly explains how luxury mechanical watches work and how Rolex operates at massive scale while keeping prices high through scarcity. The story of surviving the quartz crisis by shifting from utility to status symbol, plus the smart long-term structure of the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation, shows how to build a brand that lasts decades. Ben and David were clearly enjoying themselves throughout this five-hour deep dive, which makes it one of their best episodes.

Company Overview

Company Name: Rolex

Founding Year: 1905 (as Wilsdorf and Davis Limited)

Headquarters Location: Geneva, Switzerland

Core Business: Rolex designs, manufactures, and sells high-quality mechanical wristwatches, renowned for their precision, durability, and iconic status as symbols of success and achievement.

Significance: As the leading Swiss watchmaker, Rolex commands a 30% revenue share of the Swiss watch industry, producing over 1 million watches annually and blending industrial-scale production with luxury branding to dominate the global market for mechanical timepieces.

Narrative

Rolex's story traces visionary entrepreneurship and strategic evolution, transforming a modest watch-importing venture into the globe's premier timepiece brand. Hans Wilsdorf, born in 1881 as a Bavarian orphan, brought an outsider's ingenuity that challenged Swiss watchmaking conventions. After losing his parents at age 12, Wilsdorf thrived in boarding school, mastering mathematics and English. This propelled him to Geneva for roles at Cuno Korten, where he absorbed watch movements, precision, and global distribution. In 1903, he relocated to London, launching Wilsdorf and Davis Limited in 1905 with financier Alfred Davis. The company initially imported Swiss movements for assembly in London, setting the foundation for Rolex's ascent.

Hans Wilsdorf (1905–1960): Founding Vision and Innovation

Hans Wilsdorf built the company from a watch importer into a Swiss icon. Starting as Wilsdorf & Davis in 1905, he trademarked "Rolex" in 1908, emphasizing precision with the first wristwatch chronometer certification (1910). Relocating to Geneva amid WWI tariffs, he pioneered the Oyster waterproof case (1926) and Perpetual self-winding (1931), creating the Oyster Perpetual Chronometer. Under Wilsdorf, Rolex navigated WWII neutrality, supplying Allied forces and forging ties with explorers. By 1945, he launched the Datejust and established the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation, ensuring perpetual independence. His era defined Rolex as durable, innovative tools, producing 150,000 certified chronometers by 1950.

André Heiniger (1963–1992): Lifestyle Branding and Global Expansion

André Heiniger, Wilsdorf's protégé, steered Rolex toward luxury amid the quartz crisis. Joining in 1948, he became CEO post-Wilsdorf, declaring "We're in the luxury business, not watches." He introduced "tool watches" like the Submariner (1953), Explorer (1953), and GMT-Master (1955), targeting adventurers. Campaigns like "Men Who Guide the Destinies of the World" featured Eisenhower; partnerships with IMG enlisted golfers like Palmer and Nicklaus. Facing quartz (1969), Heiniger resisted full pivot, limiting Oysterquartz while emphasizing mechanical heritage. His tenure transitioned Rolex from utility to aspiration, vertically integrating and sponsoring events like Wimbledon, solidifying 30% Swiss share by retirement.

Patrick Heiniger (1992–2008): Vertical Integration and Luxury Pivot

Patrick Heiniger, André's son, consolidated Rolex as a luxury powerhouse. As commercial director (1986), he navigated post-crisis growth, acquiring Aegler (2004) for in-house movements and centralizing production into four mega-facilities. This ensured uniform quality amid rising demand, boosting output to ~800,000 units annually. He resisted overproduction, fostering scarcity. Patrick's focus on engineering (e.g., Parachrom springs) and secrecy preserved mystique, yielding $5B+ revenue by 2008.

Bruno Meier and Gian Riccardo Marini (2009–2015): Stability and Transition

Post-Patrick, CFO Bruno Meier (2009–2011) stabilized operations amid the financial crisis. Veteran Gian Riccardo Marini (2011–2015) refined operations, enhancing tool watches and digital presence. Both leaders preserved continuity, navigating recovery with modest growth.

Jean-Frédéric Dufour (2014–Present): Modern Dominance and Scarcity

Dufour, ex-Zenith, amplified global prestige, acquiring Bucherer (2023) for retail control. Campaigns like "Every Rolex Tells a Story" blend heritage with innovation; production nears 1.2M units, revenue ~$11B. He manages waitlists while emphasizing sustainability and arts philanthropy, cementing Rolex's 30% market dominance.

Timeline

1881: Hans Wilsdorf is born in Kulmbach, Bavaria.

1893: Wilsdorf loses his parents at 12, enters boarding school, and excels in math and English.

1900: Wilsdorf moves to Geneva, works for a pearl merchant, then joins Cuno Korten, a watch exporter.

1903: Wilsdorf moves to London, works for an unnamed watch company.

1905: Wilsdorf and Alfred Davis found Wilsdorf and Davis Limited in London to import Swiss watches.

1908: Wilsdorf coins the brand name "Rolex," trademarked in Switzerland.

1910: Rolex earns the world's first wristwatch chronometer rating from the School of Horology in Switzerland.

1914: Rolex receives the first Kew-A certification for a wristwatch, proving its precision.

1915: Wilsdorf and Davis rebrand as Rolex Watch Company Limited due to anti-German sentiment in Britain.

1916: Rolex begins assembling watches in Bienne, Switzerland, near Aegler's movement workshop.

1919: Rolex moves its headquarters to Geneva, Switzerland.

1920: Rolex and Aegler exchange shares, with Hermann Aegler joining Rolex's board.

1926: Rolex registers the "Oyster" name for its waterproof case; Tudor launches as a more affordable brand.

1927: Mercedes Gleitze wears a Rolex Oyster during her English Channel swim, featured in a Daily Mail ad.

1931: Rolex patents the perpetual self-winding rotor; introduces the crown logo and Rolesor (gold-steel mix).

1936: Aegler becomes exclusive to Rolex, renaming itself the Aegler Manufacture of Rolex Watches.

1940: Rolex supplies dive watches to the Italian Navy via Panerai; resumes exports to Britain via Spain and Portugal.

1944: Hans Wilsdorf's wife Ana dies; he establishes the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation, transferring his ownership.

1945: Rolex launches the Datejust and Jubilee bracelet; gifts a Datejust to Swiss General Henri Guisan.

1946: Rolex gifts a Datejust to Winston Churchill, followed by Dwight Eisenhower in 1947.

1953–1955: Rolex launches the Explorer, Submariner, GMT-Master, Turn-O-Graph, and Milgauss, targeting specific lifestyles.

1960: Hans Wilsdorf dies; André Heiniger becomes CEO.

1963: Rolex names its chronograph the Daytona, tying it to the Daytona Speedway.

1967–1970: Rolex launches the "If You Were" campaign, emphasizing lifestyle and achievement.

1969: Seiko launches the Astron, sparking the quartz crisis; Paul Newman receives a Daytona from his wife.

1978: Rolex releases the Sea-Dweller 4000 amid the quartz crisis.

1986: Italian dealers drive a craze for "Paul Newman" Daytonas, sparking the collector market.

1989: Rolex and Patek Philippe achieve record sales, capitalizing on the mechanical watch renaissance.

1992: Patrick Heiniger becomes CEO, focusing on vertical integration.

2004: Rolex acquires Aegler for ~1 billion Swiss Francs.

2008: Patrick Heiniger steps down due to health issues; Bruno Meier becomes CEO.

2011: Gian Riccardo Marini becomes CEO.

2023: Rolex acquires Bucherer, a major retailer, for a rumored $5 billion.

Notable Facts

Market Dominance: Rolex accounts for 30% of the Swiss watch industry's revenue, far surpassing competitors like Cartier and Omega (7.5% each).

Production Scale: Rolex produces over 1 million watches annually, a scale unmatched by other high-end watchmakers, yet maintains a luxury perception.

Charitable Ownership: The Hans Wilsdorf Foundation, owning 100% of Rolex, donates ~300 million Swiss Francs annually, much of it to Geneva residents.

Vertical Integration: Rolex consolidated production into four advanced facilities, forging its own metals (e.g., 904L Oystersteel) and making custom machinery.

Cultural Icon: Rolex's association with figures like Eisenhower, Churchill, and Paul Newman, and events like Everest and the Apollo missions, cements its status as a symbol of achievement.

Financial & User Metrics

Revenue: Estimated at ~$11 billion annually.

Units Sold: ~1.1–1.24 million watches per year.

Average Selling Price: ~$13,000 per watch at retail.

Market Share: ~30.3% of the Swiss watch industry's revenue, compared to 7.5% for Cartier and Omega.

Operating Margin: Estimated at ~40%, higher than the industry average of 29%.

Cash Reserves: Likely $50 billion or more, accumulated from decades of strong cash flow, though the company discloses no exact figures.

Employee Count: ~16,000 worldwide, with ~9,000 in Switzerland.

The 3 Key Features That Make a Rolex

Rolex's superiority stems from three pioneering innovations combined in the 1930s: the Oyster (waterproof case), Perpetual (self-winding mechanism), and Chronometer (precision certification).

Oyster, patented in 1926, revolutionized watchmaking with a hermetically sealed case resistant to water, dust, and elements. Its screw-down crown and back prevented ingress, tested by Mercedes Gleitze's English Channel swim.

Perpetual, introduced in 1931, added self-winding via a rotor capturing kinetic energy from wrist motion. This eliminated daily winding and preserved the Oyster's seal.

Chronometer certification ensured precision, with Rolex pioneering wristwatch chronometry in 1914, guaranteeing accuracy within seconds daily.

Hans Wilsdorf's vision integrated these elements: precise movements in waterproof, self-sustaining cases. This trio enabled tool watches for explorers, divers, and pilots, creating an unbreakable, precise, user-friendly product that outlasted competitors.

Impact of WWII on Rolex

World War II transformed Rolex from a niche wristwatch maker into a global icon. The war's demands for accurate timepieces in extreme conditions amplified wristwatch utility. Rolex supplied watches to Allied forces, particularly RAF pilots who needed instruments to withstand pressure changes and harsh environments. The Oyster Perpetual proved vital in air battles for navigation and synchronization. Rolex also made dive watches for the Axis Italian Navy.

Post-war, returning GIs and a booming American economy created massive demand, positioning Rolex as a symbol of victory. Rolex's Swiss neutrality allowed uninterrupted production while the company emphasized Swiss heritage to counter anti-German sentiment. Culturally, WWII cemented Rolex's association with heroism, paving the way for "tool watches" like the Submariner and Explorer. The war redefined Rolex as enduring excellence amid chaos.

The Quartz Crisis

The quartz crisis (1970s–1980s) decimated Swiss watchmaking, shifting from artisan craftsmanship to technological disruption. Viewed through Clayton Christensen's "jobs to be done" lens, it reveals how quartz redefined timekeeping's purpose, obsoleting mechanical watches' utility while birthing luxury as a new "job."

Chapter 1: Pre-Crisis Artisan Dominance (1940s–1960s) Switzerland commanded 85% of global watches (1945), producing 19 million units via 2500 fragmented firms employing skilled artisans in établissage systems. The "job" involved precise timekeeping for daily life—wristwatches as essential tools. Rolex exemplified this with Oyster Perpetual Chronometers, blending waterproofing, self-winding, and accuracy for professionals (e.g., pilots, divers). High labor costs and complexity sustained premiums, but the market rewarded craftsmanship over efficiency.

Chapter 2: Quartz Emergence (1960s–1970s) Quartz, invented at Bell Labs (1927) but miniaturized via transistors/integrated circuits, vibrated crystals at 32,768 Hz for superior accuracy. Seiko's Astron (1969) launched at car prices, initially inaccurate (+/-5 seconds/day) but rapidly improved. Initially a sustaining innovation (better timekeeping), it disrupted by slashing parts (from 200+ to dozens), enabling automation and low-cost assembly in Japan/Hong Kong. The "job" evolved: consumers sought cheap, precise timepieces, not artistry. Swiss firms, including Omega, panicked, flooding markets with quartz models and eroding brands.

Chapter 3: Crisis Peak - Artisan Market Collapses (1975–1985) By 1980, Switzerland's share plummeted to 15%; firms dropped from 2000 to 500. Quartz captured 31% of units (1979), Hong Kong exported 126 million (1980), Japan surpassed Switzerland (1981). Mechanicals became functionally obsolete—quartz offered cheaper, accurate, battery-powered alternatives. Rolex explored Oysterquartz but resisted full pivot, preserving mechanical ethos. The "job" fractured: timekeeping went digital (LCD/LED from Seiko/Casio), commoditizing low-end; Swiss faced extinction, with conglomerates like Swatch Group rolling up survivors.

Chapter 4: Renaissance - New Job Emerges in Luxury (1980s–1990s) Quartz's banality created opportunity: mechanicals filled a new "job"—signaling status, craftsmanship, heritage. Auction houses valued rarity. Blancpain revived as mechanical-only ("No quartz since 1735"). Rolex leaned in, emphasizing engineering and lifestyle (testimonees like Federer). Secondary markets boomed (Paul Newman Daytona craze, 1986), turning watches into investments. The artisan market transformed: technology obsoleted utility, but scarcity/artistry birthed luxury, where "jobs" like aspiration trumped function.

Chapter 5: Legacy - Technology vs. Artisan Equilibrium (1990s–Present) Today, Swiss mechanicals capture 40% of global watch revenue despite 2% units, Rolex dominating 30% via branding/scale. Quartz/smartwatches (e.g., Apple) own functionality; mechanicals thrive in prestige. Lesson: disruptions redefine jobs—Switzerland survived by pivoting from timekeeping to symbolism, proving artisan markets endure when technology commoditizes utility, but only through reinvention.

Most Notable Watches from Rolex: Introduction, What's Special

Datejust (1945): First self-winding waterproof chronometer with date window; iconic Cyclops magnifier (1953); symbolizes post-WWII luxury, worn by Eisenhower; versatile dress watch blending elegance and innovation.

Submariner (1953): Pioneering dive watch, waterproof to 100m (later 300m); rotating bezel for timing; linked to Cousteau, Bond; epitomizes durability, spawning variants like Sea-Dweller (1967, helium valve for saturation diving).

Explorer (1953): Honored Everest summit (Hillary/Norgay wore prototype Oyster Perpetual); shock-resistant, luminous dial for extreme conditions; simple, robust design for adventurers; Explorer II (1971) added 24-hour bezel for polar exploration.

GMT-Master (1955): Dual-time zone watch for Pan Am pilots; rotatable 24-hour bezel (Pepsi colorway iconic); tracks multiple time zones; evolved to GMT-Master II (1982) with independent hour hand.

Milgauss (1956): Anti-magnetic watch for scientists (e.g., CERN); withstands 1,000 gauss; discontinued in 1988, relaunched in 2007 with lightning-bolt second hand; niche appeal blending science and style.

Daytona (1963): Chronograph for racing (named after Daytona Speedway); tachymeter bezel measures speed; Paul Newman dial (1960s) sparked collector craze; manual-wind evolved to automatic (1988); ultimate status chronograph.

Sea-Dweller/Deepsea (1967/2008): Extreme dive watches; Sea-Dweller to 610m with helium valve; Deepsea Challenge (2012) survived Mariana Trench (10,908m); pushes engineering limits for deep-sea exploration.

Ad Campaigns Throughout Rolex's History

Rolex's advertising evolved from functional demonstrations to aspirational storytelling, building a timeless brand of achievement and precision.

Mercedes Gleitze Channel Swim (1927) Rolex's first major ad featured Mercedes Gleitze's English Channel swim, proclaiming the "wonder watch that defies the elements" on the Daily Mail's front page. This campaign established functional proof as Rolex's foundation, demonstrating waterproof capability through real-world testing.

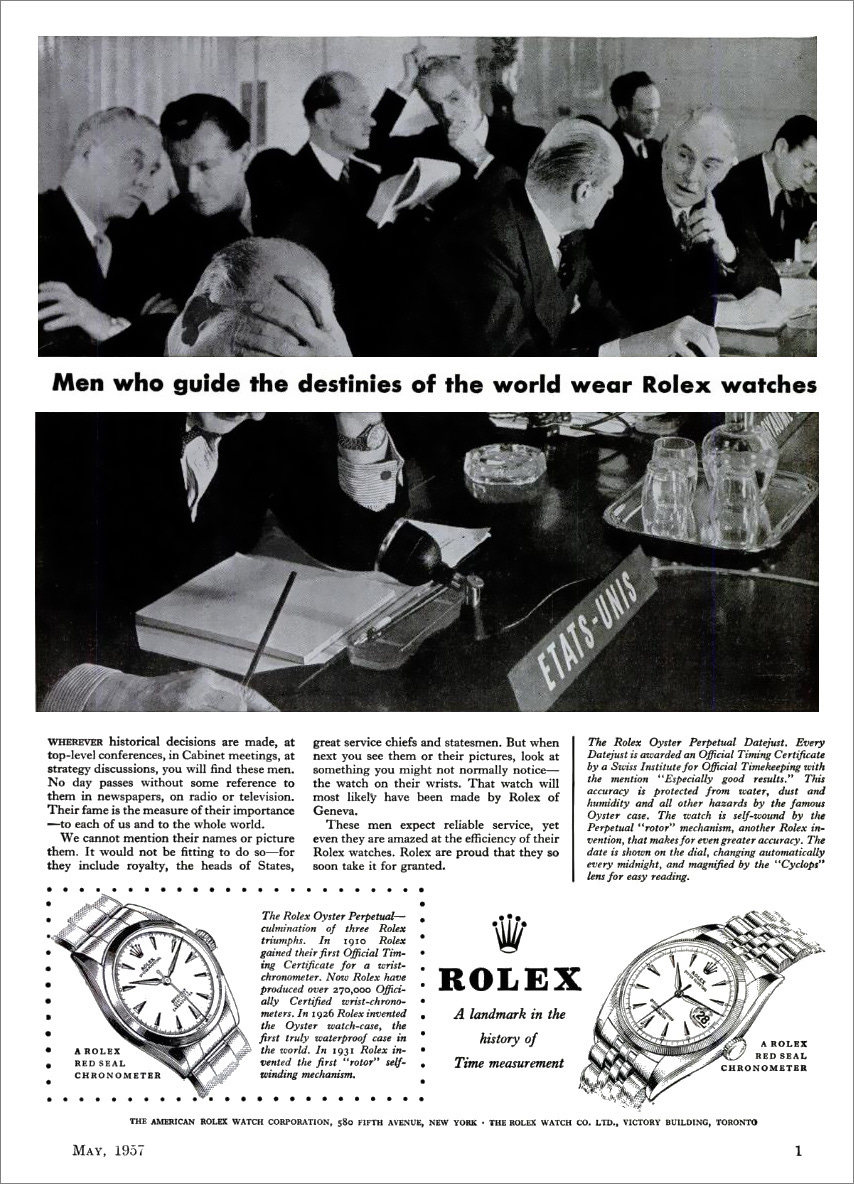

"Men Who Guide the Destinies of the World Wear Rolex" (1950s) This series featured Eisenhower and Churchill, showcasing the Datejust as presidential symbols. The campaign solidified Rolex as success emblems, leveraging post-WWII American prosperity and GI affinity for the brand.

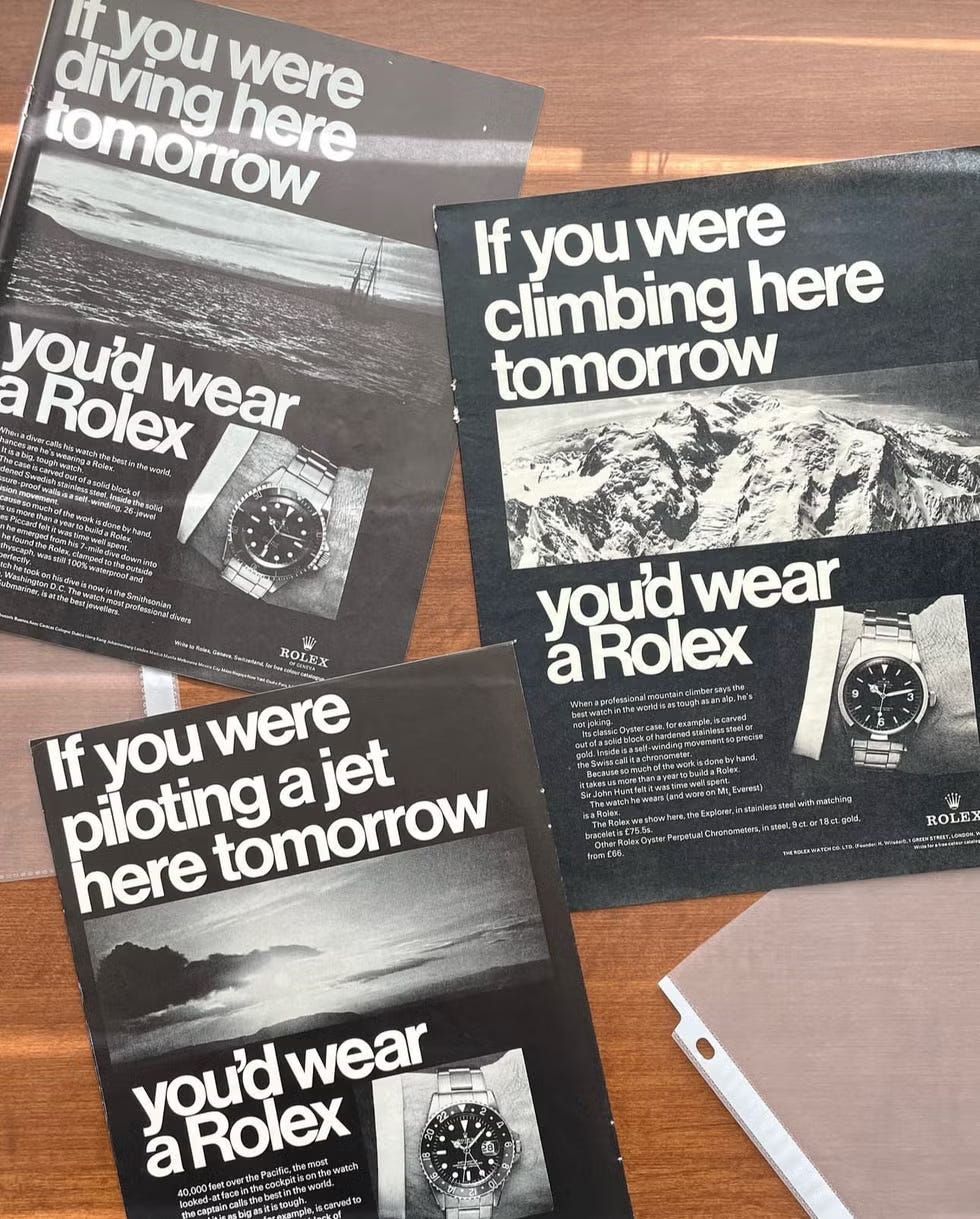

"If You Were" Campaign (1967) Depicted aspirational scenarios like flying Concorde or speaking at the UN, pairing GMT-Master and Submariner with bold Helvetica typography. This campaign shifted Rolex from functional tool to lifestyle aspiration, targeting adventurous professionals.

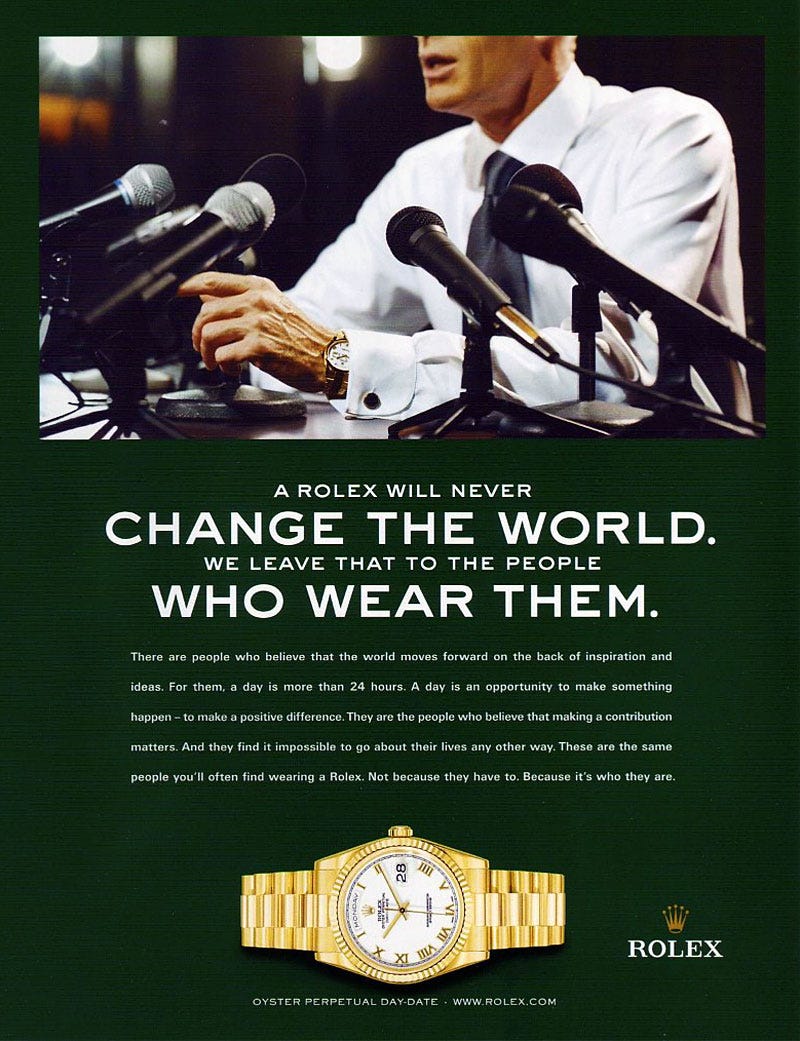

"A Rolex Will Never Change the World" (1970s) Launched during the quartz crisis, this campaign emphasized human achievement over technological innovation, stating "We Leave That to the People Who Wear Them." It reinforced Rolex's mechanical heritage when competitors pivoted to quartz.

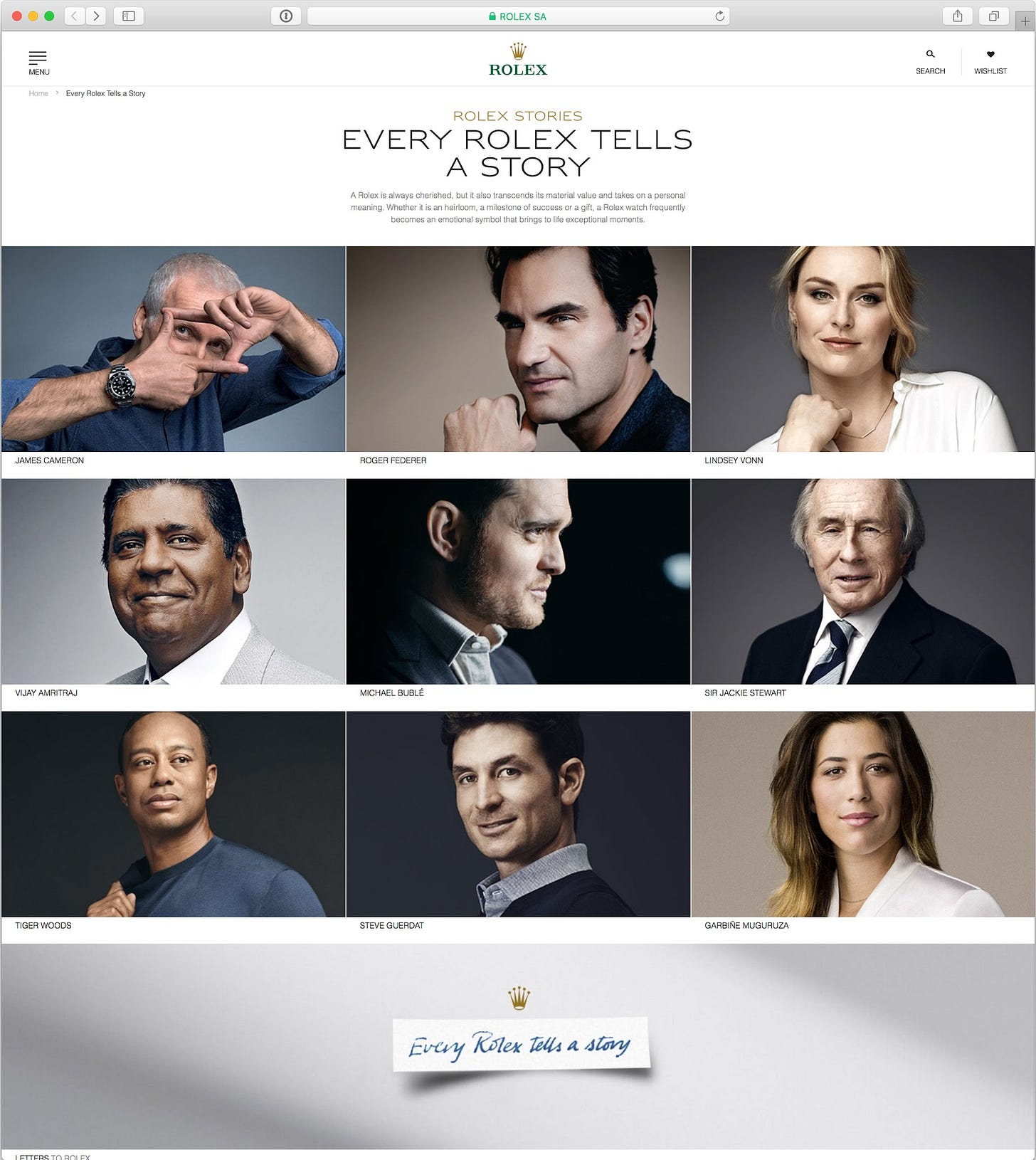

"Every Rolex Tells a Story" (2000s–Present) Features testimonees like Federer, blending heritage with innovation. Combined with scarcity marketing and influencer partnerships, this campaign targets millennials while maintaining exclusivity through waitlists as status symbols

.

Rolex's campaigns evolved from functional proof to lifestyle aspiration, creating $11B in revenue through strategic brand positioning.

The Modern Watch Craze

The modern watch craze originated in the 1980s amid the quartz crisis, when mechanical watches shifted from utility to collectible luxury. Italian dealers sparked frenzy by snapping up vintage Rolex Daytonas, especially Paul Newman models, driving prices from $200 to $30,000 overnight, birthing the collector market.

Growth accelerated in the 1990s–2000s with internet forums, Hodinkee, and YouTube democratizing knowledge. Post-2008, Rolex doubled U.S. marketing, targeting aspirational buyers. The 2010s boom, amplified by social media, saw hype around limited editions.

The secondary market thrives, valued at $20–$30 billion annually, with platforms like Chrono24 creating liquidity. Currently, demand outstrips supply, with Rolex waitlists years long amid $10+ billion revenue. Interesting facts: Rolex produces 1.2 million watches yearly yet dominates 30% of Swiss revenue; fakes outnumber authentics 20:1. The craze blends investment, status, and passion, evolving from 1980s speculation to global culture where watches signal success beyond timekeeping.

Hans Wilsdorf Foundation

The Hans Wilsdorf Foundation, established in 1945 by Hans Wilsdorf, the visionary founder of Rolex, serves as the sole owner of the company, ensuring its long-term stability and profitability while embodying Wilsdorf's commitment to philanthropy. Following the death of his first wife, Florence Frances May Wilsdorf-Crotty, in 1944, Wilsdorf, who had no children, created the foundation to secure Rolex's future and perpetuate its legacy.

In 1960, he transferred his 100% ownership stake to the foundation, a move that insulated Rolex from external market pressures and shareholder demands, allowing the company to focus on quality and innovation. Based in Geneva, Switzerland, the foundation operates as a charitable organization, balancing its role as Rolex's steward with significant contributions to social, educational, cultural, humanitarian, and environmental causes. This dual purpose reflects Wilsdorf's vision, ensuring "the continued operations of Rolex" while giving away "300 million Swiss francs a year, a huge portion of it just directly giving money to people in need in Geneva."

The foundation's charitable giving proves substantial, supporting over 5,500 projects each year. The foundation distributes these donations across diverse areas, including social initiatives, education, culture, humanitarian aid, animal protection, and environmental preservation, with a significant focus on Geneva.

For instance, the foundation acquired La Cour des Augustins, an empty hotel in Geneva, for 32 million francs to provide facilities for charitable organizations aiding the unhoused. Roughly one-third of its donations support humanitarian aid, one-third focus on animals and ecosystems, and one-third go to local Geneva projects, such as helping families with rent or students facing financial hardship.

Notably, animal and environmental initiatives have no geographical restrictions, reflecting Wilsdorf's explicit directive to support these causes globally. The foundation's discreet operations, enabled by Swiss laws that do not require public financial disclosure, allow it to maintain a low profile while making a profound impact, aligning with Wilsdorf's vision for Rolex to serve as both a profitable business and a force for societal good.

Key Functions:

Ownership and Management: The foundation owns 100% of Rolex, ensuring its independence and long-term focus, as Ben and David highlight: "They can have three bad years in a row and the CEO might not get fired."

Charitable Giving: Donates ~300 million Swiss francs annually, supporting over 5,500 projects in welfare, healthcare, education, culture, humanitarian aid, animal protection, and environmental causes.

Discreet Operations: Operates without mandatory financial disclosures, allowing strategic flexibility and privacy, as the hosts note: "They're one of the most secretive companies that we have ever studied."

Impact and Legacy

The foundation's structure, as a tax-exempt charitable entity, allows it to reinvest Rolex's profits into both the company and philanthropy, ensuring sustainability. Ben and David emphasize its local impact, stating, "It seems like they're just giving money away all over Geneva." Projects like the Hans Wilsdorf Bridge symbolize its influence, described as a "state within a state" in Geneva. Globally, its support for animal and environmental causes extends Wilsdorf's legacy beyond Switzerland, making the foundation one of the world's most active charitable entities.

Powers

Branding: Rolex's brand serves as its dominant power, as Ben and David emphasize its evolution from a functional timekeeper to a global symbol of success. The "If You Were" campaign and partnerships with figures like Jacques Cousteau and Roger Federer create an aspirational aura, driving demand despite functional obsolescence post-quartz crisis. This branding ensures customers pay a premium for the prestige of owning a Rolex, not its timekeeping utility.

Scale Economies: Rolex leverages its scale to achieve unmatched production efficiency and quality control, producing over 1 million watches annually with proprietary metals and custom machinery. This scale, highlighted by the 2004 Aegler acquisition and consolidation into four facilities, allows Rolex to maintain high margins (~40%) while ensuring consistent quality, a feat competitors like Omega cannot match at this volume.

Playbook

Rational Decisions Over Big Risks: Rolex avoided major gambles, leveraging strong resources (e.g., cash reserves, foundation ownership) to make prudent, logical choices, such as cautiously exploring quartz or doubling U.S. marketing during the 2008 crisis, enabling steady growth without overextension.

Continuity in Strategy: Success stems from unwavering adherence to core elements—product lineup, culture, and positioning—over decades, allowing compounding advantages and consistent brand evolution from utility to luxury.

Slow Iterations: Incremental refinements to models (e.g., subtle updates every 7–10 years) preserve timelessness, making customers feel smart as past purchases retain relevance and value, reinforcing loyalty.

Employee Loyalty: High pay, benefits, and perks foster long tenures, creating a stable, secretive workforce that minimizes turnover, preserves knowledge, and supports operational excellence.

Quintessence

David: Optimal Supply-Demand Positioning: Rolex excels at the ideal intersection of price and quantity, maximizing revenue by producing over a million units annually while maintaining scarcity-driven demand.

Ben: Redefining the Industry: Labeling Rolex as "high-end watches" misses the point—mechanical watches now serve a new "job to be done," shifting from timekeeping utility to symbols of status, craftsmanship, and aspiration, distinct from quartz or smartwatches.

Rolex serves as the entry point for newcomers to luxury watches, captivating with accessibility and prestige, yet collectors return to the brand after exploring exotics, valuing its enduring engineering and reliability. The more one studies Rolex—its history, innovations, and strategy—the greater the admiration grows.

Acquired Universe Crossover

The Rolex episode reveals recurring patterns across luxury brands and visionary companies that Acquired has profiled:

Hermès: Both founded by orphans in the 1800s who brought outsider perspectives to challenge established industry norms; both maintain ~40% operating margins through scarcity and craftsmanship positioning

Louis Vuitton: Another orphan founder from the 1800s (Louis Vuitton left home at 13) who disrupted traditional luggage design, paralleling Wilsdorf's challenge to Swiss watchmaking conventions

Meta: Hans Wilsdorf mirrors Mark Zuckerberg's strategic acquisition philosophy—both understood that market leadership requires acquiring superior external innovations rather than internal invention. Wilsdorf perfected the Oyster waterproof case (didn't invent it); Zuckerberg acquired Instagram and WhatsApp (didn't create photo-sharing or messaging)

Porsche: Both brands follow evolutionary design philosophy—a 1963 Submariner shares DNA with today's model, just as a 1960s Porsche 911 remains recognizably similar to current versions. Consistency over revolution builds intergenerational appeal and justifies premium pricing

Carveouts

David's Carveout:

Bluey, a children's cartoon by Joe Brumm and the Australian Broadcasting Company, praised for its engaging content that entertained his sick three-year-old without being grating for adults.

Ben's Carveouts:

Appearing on the Armchair Expert podcast with Dax Shepard and Monica Padman

Episode Metadata

Title: Rolex: The Complete History & Strategy of Rolex

Episode Number: Spring 2025, Episode 2

Duration: Approximately 5 hours (4:57:57)

Release Date: February 23, 2025

Related Episodes

Hermès (Season 14, Episode 2; February 19, 2024)

LVMH (Season 12, Episode 2; February 21, 2023)

Porsche (with Doug DeMuro) (Season 12, Episode 6; June 26, 2023)